With payrolls now in the rearview mirror and nothing too outlandish revealed in the general goldilocks data, traders have resumed contemplating the one question that is on everyone’s mind: how much higher (and at what pace) will rates rise before stocks are slammed?

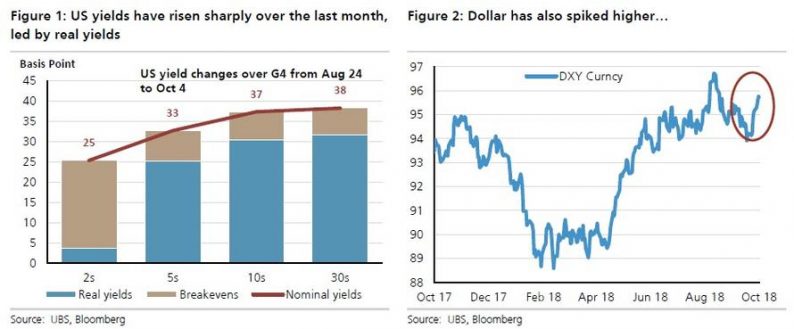

To be sure, the recent spike in US yields – driven by a combination of very strong US growth data, sturdy equity gains, rising oil prices and improving global growth expectations – and the dollar can extend in the near-term, but as UBS points out, only as long as risk tolerates this (another key aspect is the recent speed of yields increase, which “might become problematic”): naturally, once rates rise high enough there will be a capital reallocation out of stocks and into bonds. The question, of course, is what is”high enough”.

Alternatively, US yields could rise further, if global growth firms up and ex-US yields rise independently – and also if the neutral rate (r-star) is seen as rising in tandem with yields – but in that case, the dollar rally would come to an end. Which is why, to UBS long term, US yields are likely to peak in the 12 months ahead “and the higher we go from here the closer we get to that peak – at least levels-wise”.

But the biggest question whether US yields keep rising will depend on whether risky assets tolerate the spike. Earlier this year, UBS looked at the uptick in US yields and subsequent equities sell-offs of at least 5%. What the Swiss bank found is that the more gradual the rise, the higher the threshold to generate equity pain, and inversely the faster the move higher – and the latest episode has seen a 40bps move higher in just over a month – the more acute the equity reaction. Curiously, the duration and magnitude of the current yield sell-off is now virtually identical to the January 2018 episode that culminated with a 10% drop in the S&P.

That analysis, charted below, suggests we are now within a zone when yields can trigger a risk sell-off.

Leave A Comment