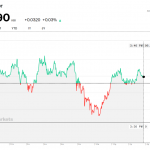

On June 26, the 10-year generic German yield closed at 24.5 basis points. It finished last week a little over 57 basis points. The similar Italian yield has risen 45 basis points to 2.05%. The short-end of the yield curve is constrained by the negative 40 basis point deposit rate. The steepening of the yield curve offsets the price erosion of banks’ bond holdings, and bank share price (in the Dow Jones Stoxx 600) have risen five percent during this period dramatic increase in long-term interest rates).

The ECB continues to try to calibrate its communication with the evolving economy and its risk assessment. It appears that the confidence of officials has outstripped their willingness to express it for fear of spurring precisely what has happened: a premature tightening of financial conditions.

Recall with or without inflation on a durable and self-sustaining path, the ECB, with Draghi at the helm, is reluctant to remove accommodation. The ECB will most likely add another 360 bln euros of assets to its balance sheet this year and more next year, even if at a slower pace. The record of last month’s ECB meeting suggested that the central bank is prepared to alter its risk assessment for an increase in asset purchases. Investors have long assumed this to be the case, and Draghi has pushed back against ideas that deposit rate should be hiked before the asset purchases are complete.

In Germany, roughly half the backing of nominal interest rates can be explained by an increase in the 10-year breakeven. In the US, the nominal 10-year yield has risen 25 bp, but the 10-year breakeven rose by only five basis points. Italy’s performance is more like the US experience. Only about a quarter of the nominal yield increase can be accounted for by the rise of inflation expectations as reflected by the breakeven.

At stake for the ECB is tweaking its forward guidance and risk assessment. In the US, the issue is still material changes in the monetary stance. Specifically, the improved growth prospects in Q2 after a disappointing Q1 (again), the strength of the non-manufacturing ISM, and the ongoing firm labor market suggests the Fed remains on course to begin shrinking its balance sheet, and continue to gradually raise interest rates.

Leave A Comment