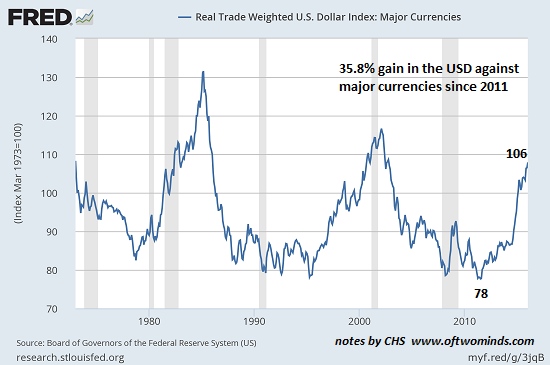

The U.S. dollar (USD) has gained over 35% against major currencies since 2011.

China’s government has pegged its currency, the yuan (renminbi) to the USD for many years. Until mid-2005, the yuan was pegged at about 8.3 to the dollar. After numerous complaints that the yuan was being kept artificially low to boost Chinese exports to the U.S., the Chinese monetary authorities let the yuan appreciate from 8.3 to about 6.8 to the dollar in 2008.

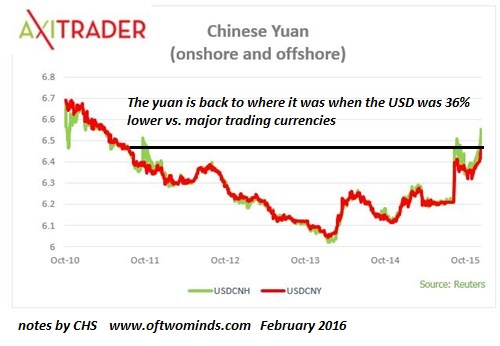

This peg held steady until mid-2010, at which point the yuan slowly strengthened to 6 in early 2014. From that high point, the yuan has depreciated moderately to around 6.5 to the USD.

Interestingly, this is about the same level the yuan reached in 2011, when the USD struck its multiyear low. Since 2011, the USD has gained (depending on which index or weighting you choose) between 25% and 35%. I think the chart above (trade-weighted USD against major currencies) is more accurate than the conventional DXY index.

Due to the USD peg, the yuan has appreciated in lockstep with the U.S. dollar against other currencies. On the face of it, the yuan would need to devalue by 35% just to return to its pre-USD-strength level in 2011. This would imply an eventual return to the yuan’s old peg around 8.3–or perhaps as high as 8.7.

Longtime correspondent Mark G. submitted this article China’s Subprime Crisis Is Here:

The dynamic is clear. A splurge of new lending can help to dilute existing bad loans, but only at a cost. This is a game that can’t continue forever, particularly if credit is being foisted on to an already over-leveraged and slowing economy. At some point, the music will stop and there will have to be a reckoning. The longer China postpones that, the harder it will be.

Mark also submitted the following commentary:

It seems the best way to assess the likely effects and outcomes is to look at what the Chinese government can control, and at what it can’t control. And we should observe at the start that the yuan is not a global reserve currency.

Leave A Comment