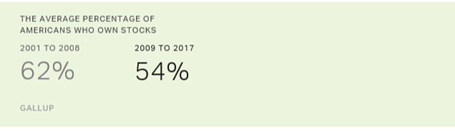

The investing masses generally are notoriously short-termed focused. Although the overall stock market notched another gain this month, stock values are still down roughly -8% from the January peak, which has caused some investor angst. Despite this nervousness, stock prices have quadrupled and the bull market has entered its 10th year after the March 2009 low (S&P 500: 666). Given this remarkable accomplishment, we can now look back and ask, “Did investors take advantage of this massive advance?” The short answer is “No.” For the most part, the fearful masses missed the decade-long, U.S. bull market. We know this dynamic to be true because data regarding stock ownership has gone down significantly, and hundreds of billions of dollars have been pulled from U.S. equity funds over the duration. For instance, Gallup, the survey, and analytics company, annually polls the average percentage of Americans who own stocks and they found ownership has dropped from 62% of Americans in 2008 to 54% in 2017 (see chart below).

Much of the negativity that has dominated investor behavior over the last decade can be explained by important behavioral biases. As I describe in Controlling the Investment Lizard Brain, evolution created an almond-sized tissue in the prefrontal cortex of the brain (amygdala), which controls reasoning. Originally, the amygdala triggered the instinctual survival flight response for lizards to avoid hungry hawks and humans to flee ferocious lions. In today’s modern society, the probability of getting eaten by a lion is infinitesimal, so rather than fretting over a potential lion slaughtering, humans now worry about their finances getting eaten by financial crises, Federal Reserve interest rate hikes, and/or geopolitical risks.

Even with the spectacular +300% appreciation in stock values from early 2009, academic research can help us understand how pessimism can outweigh optimism, even in the wake of a raging bull market. Consider the important risk aversion research conducted by Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman and his partner Amos Tversky (see Pleasure/Pain Principle). Their research pointed out the pain of losses can be twice as painful as the pleasure experienced through gains (see diagram below).

Leave A Comment